Is there a relationship between homelessness and suicide? It depends. Sometimes homelessness is a generational way of life that some children never escape, and for others, it is a temporary situation that may be resolved. The causes of homelessness are varied, but often are rooted in a series of traumatic experiences.

Let’s talk about trauma

What do you know about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) ? ACEs is a term gaining popularity as a way to identify and explain childhood trauma. A child who experiences physical and/or psychological abuse, neglect, violence, drug and alcohol abuse in the home, the suicide loss of a parent or friend, or other traumatic events is likely to struggle as an adult.

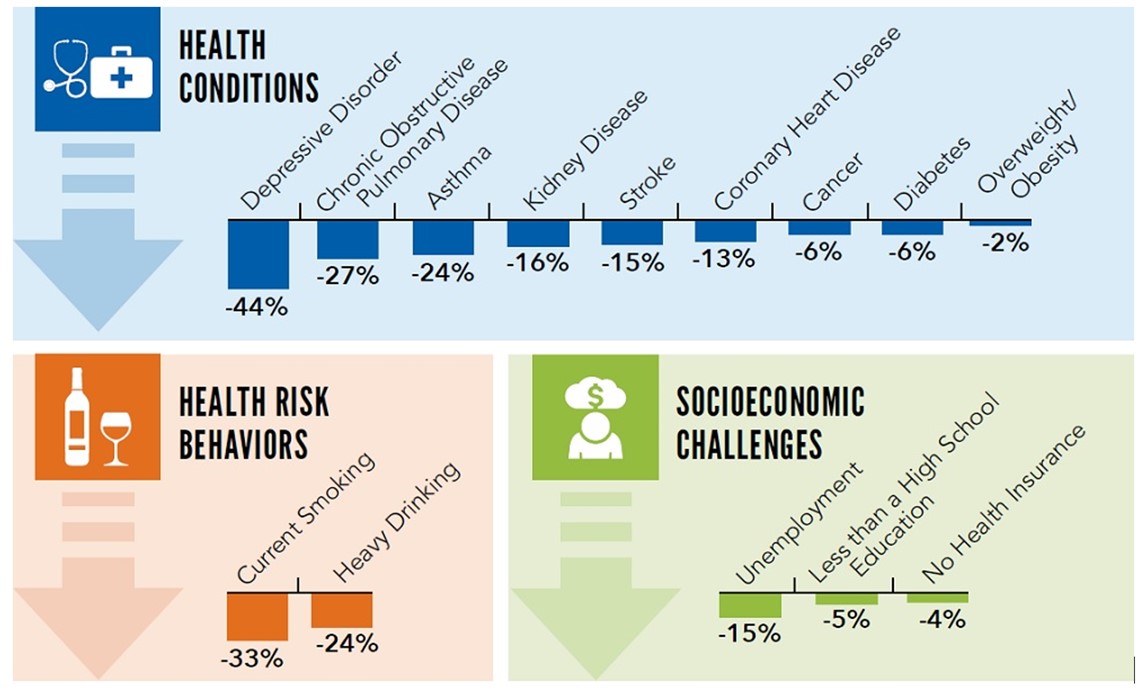

Some Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are part of life for many people, and most can lead happy, productive lives in spite of them. However, a person who has three or more ACEs is at higher risk for suicide. Researchers are learning more about how ACEs affect child development and lead to chronic illnesses in adulthood, repeating as generational patterns over time.

Prevention is possible if we learn about the steps parents and caregivers can take and how communities can participate. State policies can make a significant difference, particularly when they address childcare challenges faced by low-income families.

What studies show

How schools can help

Schools can make a difference by increasing awareness of ACEs, and training staff to identify symptoms of trauma.

Trauma is particularly challenging for educators to address because kids often don’t express the distress they are feeling in a way that’s easily recognizable — and they may mask their pain with behavior that’s aggressive or off-putting. As Nancy Rappaport, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist who focuses on mental health issues in schools, puts it, “They are masters at making sure you do not see them bleed.”

From https://childmind.org/article/how-trauma-affects-kids-school/

Know the risk and protective factors

First, school staff need to recognize risk factors for childhood trauma, and then seek to increase the protective factors in the lives of their students.

Watch this Moving Forward video to see examples of lived risk and protective factors.

Risk factors

Individual and family risk factors

-

- Families experiencing caregiving challenges related to children with special needs (for example, disabilities, mental health issues, chronic physical illnesses).

- Children and youth who don't feel close to their parents/caregivers and feel like they can't talk to them about their feelings.

- Youth who start dating early or engaging in sexual activity early.

- Children and youth with few or no friends or with friends who engage in aggressive or delinquent behavior.

- Families with caregivers

- who have a limited understanding of children's needs or development.

- who were abused or neglected as children.

- who are single parents.

- Families with

- low income

- adults with low levels of education.

- high levels of parenting stress or economic stress.

- caregivers who use spanking and other forms of corporal punishment for discipline.

- inconsistent discipline and/or low levels of parental monitoring and supervision.

- high conflict and negative communication styles.

- Families that are isolated from and not connected to other people (extended family, friends, neighbors).

Community risk factors

-

- Communities with

- high rates of violence and crime.

- high rates of poverty and limited educational and economic opportunities.

- high unemployment rates.

- easy access to drugs and alcohol.

- few community activities for young people.

- unstable housing and where residents move frequently.

- high levels of social and environmental disorder.

- Communities where

- neighbors don't know or look out for each other and there is low community involvement among residents.

- families frequently experience food insecurity.

- Communities with

Protective factors

Individual and family protective factors

-

- Families who create safe, stable, and nurturing relationships, meaning children have a consistent family life where they are safe, taken care of, and supported.

- Children who have positive friendships and peer networks.

- Children who do well in school.

- Children who have caring adults outside the family who serve as mentors or role models.

- Families where caregivers

- can meet basic needs of food, shelter, and health services for children.

- have college degrees or higher.

- have steady employment.

- engage in parental monitoring, supervision, and consistent enforcement of rules.

- work through conflicts peacefully.

- help children work through problems.

- Families that engage in fun, positive activities together.

- Families that encourage the importance of school for children.

- Families with strong social support networks and positive relationships with the people around them.

Community protective factors

-

- Communities where families have access to

- economic and financial help.

- medical care and mental health services.

- safe, stable housing.

- nurturing and safe childcare.

- safe, engaging after school programs and activities.

- high-quality preschool.

- Communities where adults have work opportunities with family-friendly policies.

- Communities with strong partnerships between the community and business, health care, government, and other sectors.

- Communities where residents feel connected to each other and are involved in the community.

- Communities where violence is not tolerated or accepted.

- Communities where families have access to

So is there a relationship between homelessness and suicide?

Childhood trauma can lead to depression and anxiety, key risk factors for suicidal ideation. If a cause of that trauma is related to homelessness, then it seems likely that there is a clear relationship between homelessness and suicide.

A

Culture of Caring: A Suicide Prevention Guide for Schools (K-12) was

created as a resource for educators who want to know how to get started and

what steps to take to create a suicide prevention plan that will work for their

schools and districts. It is written from my perspective as a school principal

and survivor of suicide loss, not an expert in psychology or counseling. I hope

that any teacher, school counselor, psychologist, principal, or district

administrator can pick up this book, flip to a chapter, and easily find helpful

answers to the questions they are likely to have about what schools can do to

prevent suicide.

A

Culture of Caring: A Suicide Prevention Guide for Schools (K-12) was

created as a resource for educators who want to know how to get started and

what steps to take to create a suicide prevention plan that will work for their

schools and districts. It is written from my perspective as a school principal

and survivor of suicide loss, not an expert in psychology or counseling. I hope

that any teacher, school counselor, psychologist, principal, or district

administrator can pick up this book, flip to a chapter, and easily find helpful

answers to the questions they are likely to have about what schools can do to

prevent suicide.